Seats at the Table

As I continue to experience a uniquely quiet and thought-provoking summer, I find myself able to spend more time cooking, doing home stewardship, and engaging in other “domestic research”. Does this herb go with this meat, or this type of cheese? Which type of battery is best for my classic sports car? How can I get those stains out of the ceiling from where the roof leaked a few years ago? What is my best sleep schedule? Let’s set up some research, and collect some data!

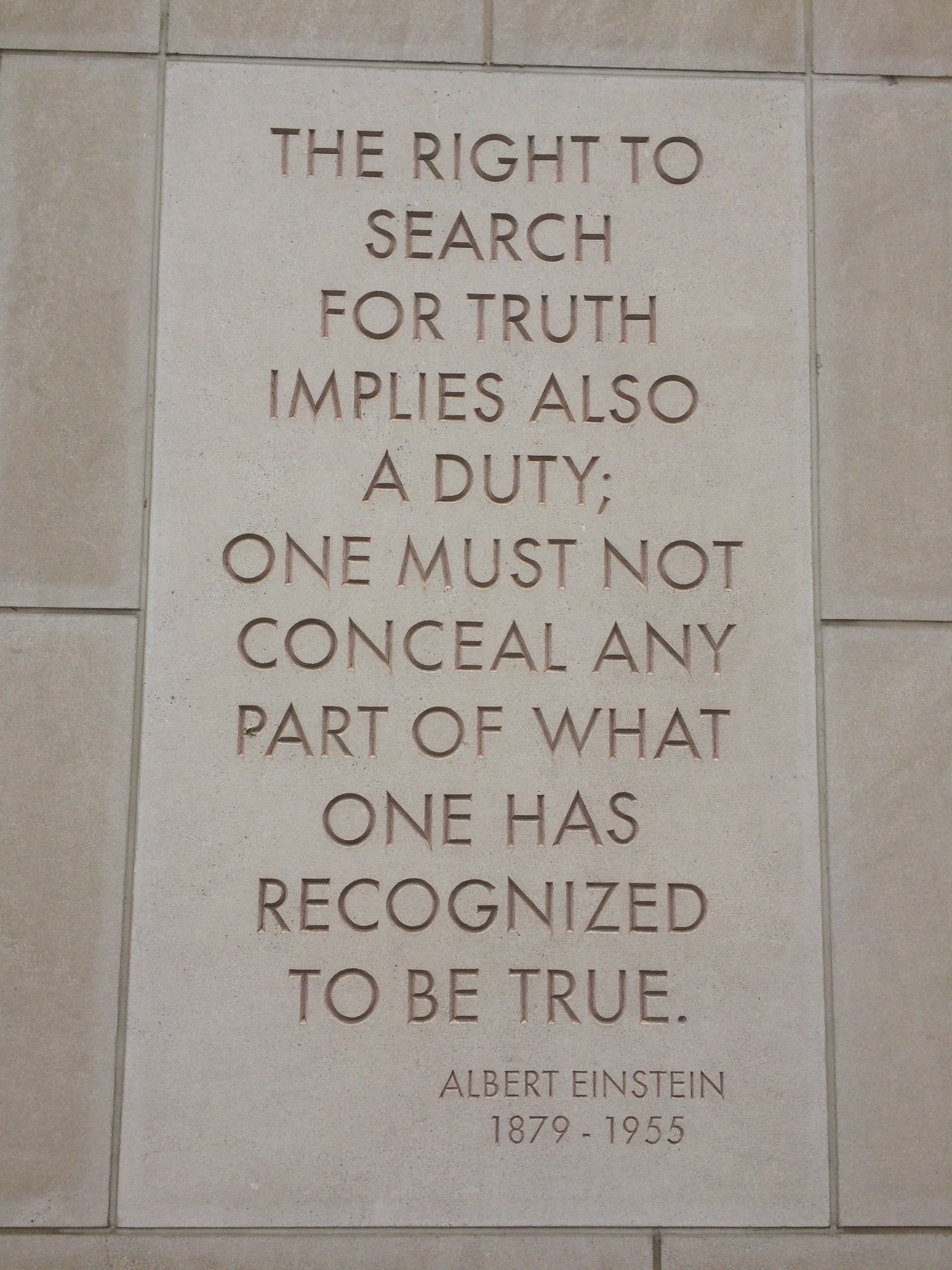

Research, I often tell the students in the lab, is an act of communication and documentation. The more unique or non-standard the research, I explain, the more the burden falls on the researcher as writer (rather than the audience) to understand the context and implications (and even relevance) of the research. I sometimes hear complaints about that burden: “That’s not fair!” (I will not digress too much on my feelings about “fairness” in this sense. No, it’s not maximally convenient to the writer. Actually, it’s much harder, and sometimes relegates work to being ignored, or non-influential, or unappreciated, or even flat-out rejected. And sometimes, that is simply unjust. But pointing out that something is inconvenient, or inequitable, or unbalanced, or unjust doesn’t mean that it’s not true.)

Over the past few weeks, I have had lots of opportunities to think about professional colleagues of mine. It might be a LinkedIn update, or a work-related email, or a professional society web update, or any of the various ways that academics engage with their professional discipline and their personal or research networks. Of course, we’re all busy, so I don’t mean to say that I am in active, daily interactions with any of them, let alone all of them. However, that’s not the point. For any subset of them, there can be a variety of events or projects that cause me to interact with or at least consider “Hey, what’s xyz up to these days?” Some folks have been moving around, so it may take me a moment to find out about where they are right now, or what they might be working on in research or campus administration. So, I may do a search on Mark, or Gary, or Mike, or Alec, or Steve. I may remember a past research project or see a news story, so I want to follow up on Harriet, or Stephanie, or Tonya, or Pamela. Normally, those of us in the university world think nothing unusual for academics to do that sort of thing. If you include me in the list, that’s a group of 10 folks. Not even that hard for a dinner reservation at a restaurant (well, when we get back to having dinner at a restaurant, but that’s another discussion for another day), if you could get us all together in between our busy schedules. We’re not all in the same discipline, after all, nor are we limited in our work obligations. That’s what happens when one becomes a full professor in engineering.

By the way, the NSF likes to collect and analyze data, so when several close friends of mine (and my daughter, over some French toast during a visit in Madison) challenged me to do some thought experiments, it was easy to go to the Survey of Earned Doctorates. One of the original versions of the question involved how well most people know about the world of academic faculty, particularly at research universities. Well, most of the people I spend time with know… because that’s who I spend a lot of my time with, and besides, anyone who knows me hears about what I do. But that’s not really a representative sample of the world, is it? (In fact, that is exactly the sort of example I’d use to say, “that’s not systematic observation!” in a stats or human factors class.) But for the rest of the world, the idea is kind of abstract and remote, and outside of their experience. So, all 10 of us being full professors in engineering departments (when we’re not being department, college, or campus-level administrators) would make us part of a group of about 11,600 folks.

However, I am also intentionally telling this story in a particular way, to build up to a particular punch line for dramatic effect. (I admit: I like doing that.) Actually, there is nothing untrue, or misleading, or even tricky about the story. I’m not picking folks that I have only seen on TV or in a movie; I’ve interacted with some of these folks this year, either on Zoom or in email or in person. But if you did see us all in a restaurant, sitting and talking about research budgets, or faculty senate actions, or the challenges of supervising too many graduate students with too little time, those topics would not necessarily catch your attention first, or surprise you the most.

We’re all Black.

Why is that important? Of those 11,600 or so engineering full professors, maybe 250 of them are Black males. Only about 50 are Black females[1]. (A male-female faculty ratio of 5:1 is not actually that surprising in engineering, so having the table be close to gender parity would be a surprise if you knew it was engineering faculty.) That’s not very many people. And to be honest, if I were asked “what can these people do to increase STEM diversity?” my answer would be fairly simple.

Exist. Do your work.

(This is my own personal version. Others may reference a quote, such as “Do what you can, where you are”. Versions of this are attributed to Arthur Ashe, or Teddy Roosevelt (who attributed it to Bill Widener).

I admit that I am not the sort of person who grabs a bullhorn to lead a crowd in an activist demonstration on any topic. (The only times I’ve used a megaphone or mic to stir up a group would be as a coxswain for a rowing team, or as a host / MC for a STEM-related research conference or public outreach event.) But I have come to a growing recognition over the years that just standing there and speaking in my own voice, in front of a class or at the conference or as host of the event, can be a very powerful statement and surprising communication. As my daughter had pointed out, if I retired tomorrow, I would be able to say that I made a difference and have left a legacy. But I’m not likely to retire tomorrow. What is changing is the sense of what work I will choose to do, and on whose terms. That is actually fairly new for me, to decide to pick my own terms and communicate my own messages, in my own way, in my own time. I’m not even completely sure what messages I will be choosing to communicate (including this one). I do recognize that the burden is on me to make the message as clear and understandable as possible. However, I am no longer assuming that, when other people don’t get or believe the message, that it must be my fault. Just letting go of that may be a key to doing my best job in answering my own question. What is my work? Not for you, or him, or her. What am I best suited for as me, in the world that is, even if I wish to design for the world that is not?

Actually, that’s a good question for everyone to ask, and not be afraid of finding a new answer.

[1] (These numbers come from NSF Table 9-25, from 2017.)

July 28, 2023

Paying for It

It is completely without irony or sarcasm that I choose to use a deliberatively (and, in some ways, disingenuously) provocative title for this entry. In fact, the very existence of this writing (and its visibility as a blog entry) is part of an evolution in my experience as an academic. Before I go any further, however, let me assure you that there is no mention of any behavior representing exchanging items of value for erotic services[1].

This entry, and other related writings, have been sitting in my to-do list for several days (or is it weeks?) now. I was very pleased and excited to find a stimulus for this writing while drinking fantastic coffee and eating delightful cherries and locally baked bread while reading the recent issues from two of my regular print subscriptions: Fast Company and Scientific American (which I don’t visit online, except to provide links to others, as I am doing here). I got to enjoy delightful interviews with scholars and actors; I learned about creative research far outside of my normal field. Should I have been upset, or simply wary, when noting that at the bottom of the page of an article on an all-women team looking at cardiovascular care are the words, “created by fastco works content studio and commissioned by Shockwave”? How about the difference between an article about ground-breaking researchers in collective neuroscience, and an article by a ground-breaking researcher in insect behavior and ecology?

A few items in my history may be of particular importance here. When I was a new assistant professor, there was still a considerable debate (as evidenced by some of the advice given to me by senior faculty) about whether junior faculty in engineering should “spend their time” traveling to (and presenting their work at) professional conferences with published proceedings, rather than devoting the effort to additional journal paper and research grant submissions. It was considered even more questionable to work with journalists and marketing people (even the university’s own “communications and marketing” offices) to help create non-technical summaries of one’s work for alumni magazines or college promotional publications. However, at the same time, I was also advised to have my work as public and visible as possible, in case—as an underrepresented minority scholar with a trailblazer status at multiple universities—a negatively biased evaluation of my case would result in a denial of promotion and tenure. (That tenure decision came, with a positive outcome over 25 years ago, in the 1990s. Whether I “earned” or “received” tenure is a debate for another time; I simply note the timing to indicate that I would be considered an established and senior professor from a prior generation to the current life of scholars who grew up with the web and smartphones.)

Perhaps it is this conflict that gives me a distinct viewpoint on current discussions of social media promotion of one’s research, or the determination and characterizations of “alt metrics” to describe a scholar’s net impact on a broader community rather than (or beyond) counting citations of scholarly journal articles by other researchers. (Perhaps it is also because my father was a car salesman, and I spent much of the first 30 years of my life relieved that I was not in sales, before I realized that journal and conference papers, and grant proposals, are type of sales pitches for the startup / small business world of the research intensive faculty member and their lab.). I have served on library faculty and primary committees evaluating both the service practice and scholarship of the university library staff; this gave me a front-row seat at both the growing tension between journal subscription costs from major publishers and the need to provide comprehensive services to the campus research community. Librarians also introduced me to the challenge of understanding what counted as a suitable “alt metric” in a rapidly evolving online world.

Let me be very clear here: I am not engaged in some wistful reminiscence of some prior and mythical golden age. (Discussions of nostalgia, and the distinctions between positive and negative views of memories and past experiences, has been of some interest in recent popular media as well as research studies. Whether or not you gravitate to this article from a mental health site in the UK, or this article in the Atlantic, or this publication from Elsevier, or this piece in Vox, or this paper in the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database, all from 2023, actually undergirds some of the thesis of this entry.). I am also not complaining about some evil group of bloodthirsty folks leeching off the honest work of others and expecting exorbitant incomes from it. I am, of course, a university professor, and I have been accused of such leeching myself. For years, I had shunned the concept of “lowering myself” to submitting articles to journals that required “page charges” for publication of accepted papers. Conversely, I had to explain to non-academic friends that academics generally did not receive royalties for our journal papers, and in fact, often had to pay for publication. And of course, I recognized that paying conference registration fees to attend a professional society meeting (and obtain the published proceedings), let alone the travel expenses for such meetings, were an important and necessary element of the public visibility and professional networking in my field that was essential to grad student recruitment, nominations for national awards and service to the organization, profession, and broader society. Success as a faculty member meant that I had plenty of grant money to go to multiple conferences without asking my department for travel allowances… even though the net cost was much higher than page charges, I enjoyed the effort and expense more.

So much has changed in the past 7-8 years… after living and working outside academia for a year (providing service to the US government based on a highly competitive national fellowship), I began to think a lot more intensively, and differently, about public communications of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) to the vast majority of the population who do not have degrees, fluency, or understanding of STEM topics or research processes. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many researchers were forced to reassess how we promote and highlight our research without the ability to present our work publicly. As I also learned from discussions with my children (who both use digital technologies extensively, but consider themselves firmly in the realm of arts and humanities—my son as musician, DJ and music recorder / promoter; my daughter as humanist scholar of computer game cultures), the world of social media and networks have thrown many job categories and established market forces into maelstrom. Gig economies, streaming services, password access sharing, paywall backdoors… we demand that creative persons get paid their worth for their art and performance, but others don’t want to pay the costs for such support in a world without newsstand and subscription sales or page-size advertising revenues.

With some trepidation, I stepped into this new (for me) world of “commissioned content”. I would say that I’m pretty good at presenting material orally, and I’ve been told I have a great voice and style for people to listen to and watch for lecture material, panel presentations, or interviews. However, I’m not as fluent with the journalistic craft of hook and explanation and market connection for a general audience. So, was it evil for me to respond to an invitation for a commissioned piece regarding my involvement in STEM education and engagement, or an innovative multimodal style for presenting systems engineering material, or our prior work looking at chronic care systems for traumatic brain injury? All of these projects have been presented in conferences with published proceedings… but how many people see them? More importantly, where is the proper line drawn? Should my same trepidation extend to page charges for a requested open access paper on remote physiological monitoring? Should I be upset that my “commissioned articles” help pay for the animators, journalists, and voice actors to continue their jobs—in some cases, creating new forms of presentation that I would not have been able to do at all, or not within my time or energy or skills budget.

As a journal editor, I have had a tremendous and frustrating period of time trying to get reviewers to evaluate manuscript submissions. Conversely, authors are thrilled when I tell them that there are no charges to them for article publication. As a researcher, I evaluate the cost of conference registrations and hotel reservations for professional meetings that are at the core of my research, versus ones that might have great visibility for others. As a recognized and visible scholar in my field and at my university, I take note that an analytics firm ranked Purdue as #10 in the world on global university visibility in this evolving and complex online world… and wonder if my ventures into commissioned content may have contributed just a little bit? (No, there is no known relationship between myself, any member of my family, and the firm that published this ranking.). It’s probably more the basketball and football teams, but we take the visibility we can get, right?

Or is it that we get what we pay for?

[1] With the possible exception of exhibitionism, which could be associated with the thrill of having one’s name, image or likeness publicly presented in a media representation. This might include a reposting of a blog entry or sharing of a video link, as well as an authored publication in a high impact factor journal or magazine.

Share this: