Weekend Balance #2: Cassandra’s Postcards

Curiously, the concert that I left work to attend last night was something I discovered almost exactly one week earlier (even to the same clock time). The group I went to see was Black Violin, two classically trained violinists who are a) black, from Ft. Lauderdale; b) insistent on thinking outside of the box; and c) have a strong alternative vision of how the world can be different than it is, beyond existing stereotypes or interpretations. (Yes, the highlighted words and links are in fact the names of their albums. Go listen.) Last Friday, I was on the train to spend the New Year’s holiday in my hometown of Philadelphia with friends. I had put on the music just for some simple enjoyment, and found myself transformed and emotionally intense and resonant. (Yes, it’s also when I found out about their concern in Washington, DC last night.)

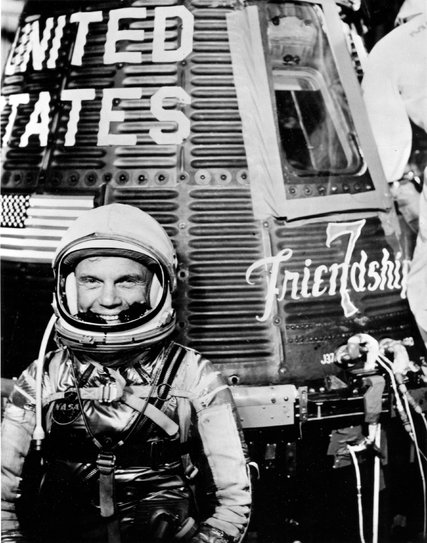

Black Violin, with the National Symphony Orchestra, Feb 6, 2017

One of my favorite descriptions of my approach to the world was provided by a GROUPER a couple of years ago, during a 1:1 meeting at a conference. (I can still see the design of the French patisserie / café in my memory.) The description was that I live part of my existence in the future, but the nice part is that I “send postcards”. This is a delightful image, but it hides a painful and problematic truth: not everyone can receive “postcards from the future,” or even know that they exist. I used to think this was a simple problem of better explanation, but I have had to come to the recognition that there is more at play. An alternative metaphor comes from my son, who once made a surprised and surprising revelation once when watching me dance to a piece of music to which I resonated very strongly. He admitted that he had thought that I simply didn’t have a very good sense of rhythm. Then, as he got older and started thinking more seriously about music composition and production as a career, he listened to more music, more often, at a deeper level. His statement at a friend’s house was with a type of confused awe: “You’re trying to dance to all of the notes, not just the normal beat.”

One of my favorite and most inspirational books of my life is called Cyteen, for a number of reasons (including some too complex to go into here). I am particularly taken by one of the descriptions of a major protagonist’s sense of their life’s work… that, if they are devoted and dedicated to their passion and their gifts and their uniqueness, because of and not simply despite their unique or alternative make-up, they may have the opportunity to someday speak their “Word,” their major contribution to history’s arc. While Speaking Words to History sounds pretty cool (at least for my sense of doing what I was built to do), it comes at a major, even profound cost. I am drawn most to the myth of Cassandra, who was cursed for defying the god Apollo (isn’t that usually how things like that turn out?) by being able to see and foretell the future, but being unable to alter it, and being doomed to have others not believe her when she told them. (I have to hand it to Apollo, though: that’s a pretty exquisite form of sadistic torture. But really, just because she turned you down for a date? I mean, you’re a god and all…)

Poor Cassandra. (From Wikipedia page, public domain image: Cassandra (metaphor)

It’s really hard to explain to GROUPERs the process of finding and sending postcards from the future, and more importantly, I don’t think it’s a proper thing for me to insist that they do so. For nearly all of the students I’ve met, it’s not the right lesson to be teaching, and there are certainly a wide range of valid and important jobs that one can take on without invoking divine curses. Having someone who can simply receive the postcard, and translate part of it, is worth a lot. For example, our current experiences of politics, local and national security, and even the nature of honest communication is based on elements of situational context, information cues, and media characteristics of different information and communication technology channels. We’re asking about tolerance and acceptance of new communications media in various organizations. That sounds like a really great research project, especially when combining new forms of social messaging as various types of an advanced, or evolved, model of email (written electronic communication), or other group interactions (with or without audio and video capabilities). It might still be considered a bit ahead of the curve, or timely, because we’re in the midst of it now. But consider a study of organizational acceptance of alternative media channels conducted in 1992, fully 25 years ago. That’s before there were any iPhones, or web browsers, or T1 lines (or many of my students). No graphical email or tweets with emojis. Do the questions even make sense? For most people, not really. (At least that’s the memory of reviewer comments for the Taha and Caldwell, 1992 submission to the Human Factors Society conference.)

Back to the train last Friday. Imagine me trying to dance to all of the notes as the train pulls into (and then out of) Philadelphia as I continue my journey. The lights of Philadelphia’s Boathouse row are still holiday festive. I am crying my resonance to the music playing in my ears. I finally feel like a type of homecoming has occurred, one that I had sought in vain for nearly 40 years. In the midst of this, an insight. Normally, I wouldn’t tell anyone, or I’d write it up piecewise in journal papers. Not this time. I’m going to show you the postcard here.

View #1: The Spectrogram

A few years ago, Jeremi London (not the actor) and I worked on a model of STEM education based on the concept that what we in fact try to teach engineers in order to be functional, productive engineers is not a single thing, but a large matrix of skills, habits, attributes, and techniques. Different courses supposedly load on different matrix elements, and different students have different strengths and weaknesses in those elements. I visualize this as a type of dynamic matrix of peaks and valleys, as you might get in a audio spectrogram. What we might think of as intelligence or skill or functionality is actually an aggregation of those peaks and valleys across that range of matrix elements: a person’s functionality is, generally, how well their peaks map onto the things they need to do on a daily basis. Zero functioning is actually hard to imagine, and if most of the population was in fact functioning at zero, we might not even see it as a relevant matrix attribute element to consider. (If someone had a peak there, would we even think about it as a peak? Consider the question of tetrachromats.) For the sake of analysis and comparison, it’s important to both retain the spectrogram as a matrix, and also consider a simplified representation of it. You could call it IQ or something. Let’s just describe it as the determinant of the functionality matrix.

View #2: The Bowl

Some of you know that I have a deep, longstanding, and personal interest in questions of neurodiversity: creating models of acceptance, encouragement, and tolerance for people with different sets of skills and forms of excellence. (This isn’t just a “feel good” about diversity and tolerance as a moral issue. This is about benefitting from excellence where it is found, including functionality peaks due to alternative wiring that represent “signs of life” not common in the general population. Well, if you’re training PhD students, that’s not a bad thing to look for: higher, and more distinct, functionality peaks than exist in the general population. After all, not that many folks get PhDs.)

So, the more your spectrogram pattern of peaks and valleys differs from the standard version (not just higher peaks, but peaks in different places), the less “standard” you are. (Standard, in this case, represents not just the population norm of the matrix determinants, but the modal matrix pattern.) In an extreme case, someone with a whole lot of peaks in places where standard people are close to zero, and very low functioning where standard people have peaks, would find it exceptionally hard or impossible to communicate with standard folks at all. (The concept of “communication” here might work as a multi-dimensional convolution integral, or a multiplication of functions against each other. You don’t worry about that just now, unless you really want to.) The more non-standard a person is, the further their pattern is from the standard pattern, and the more overall capability and functionality it might take to compensate for the mismatch, and be seen as equivalently functional as the modal, standard person. If we considered a function where the matrix determinant was the height, and the difference in pattern was a radius (different types of different patterns would be angles, so we’re in polar coordinates), the “bowl” would be a surface of “equivalent perceived functionality,” with an edge being at a place where someone, no matter how many peaks they had or how profoundly high those peaks are, could not interact with standard folks well enough to be seen as functional. (So, you can’t see in our standard visual spectrum? Well, we think you’re blind, even if you have a great visual experience of radio waves. Too bad if you can hear and sing the vibrations of the planet. We work in 200 – 4000 Hz, thank you, and if you can’t hear or produce in that range, we won’t hear what each other is saying. Literally.)

View #3: The Disk

Another of the elements we have been playing with in the lab gets the shorthand description of “The Six Dimensions of expertise,” with a corollary of “the disk”. As we described the matrix above, there are lots of different ways we could organize the elements of the matrix of ways people are good at different things. They may be socially skilled and charismatic; they may be great with tools and interfaces; they may enjoy structured rules and processes; they may enjoy mathematical analysis and quantitative exploration. There are other ways to slice skills up into different collections, but there’s been a lot of work recently into “four-quadrant” cognitive styles inventories that are used in organizational assessment. For the purposes of this discussion, all this tells us is where in the spectrogram the matrix elements of your peaks and valleys are likely to be found. Useful, if we want to do systematic comparisons of different patterns of functioning (and convolutions of functionality for communication or information alignment). Which is the “right” four-quadrant model? That’s not a proper question; it’s kind of like asking what is the “right” set of compass directions. We agree on one for the purposes of discussion, even though there isn’t even alignment between magnetic and geographic compass directions, and it’s even possible that we could have a situation where magnetic south points towards geographic north.

View #4 = Function (#1:#3)

What I’ve described for each of the views above is far from a standard description of how we consider psychological concepts of intelligence, personality, functionality, or cognitive diversity. Lots of researchers toil very intensely in intelligence assessment or engineering aptitude evaluations, or the genetic contributions to Asperger’s syndrome, or refinements of MMPI or Myers-Briggs inventories (to use examples of standard questions in each of the three views). Mathematically, however, what I have laid out can be combined (although it’s extremely hard to draw the picture in three dimensions). Imagine the spectrogram matrix (#1) of a “standard average person” (both in terms of normative / neurotypical wiring rather than autistic spectrum, and in terms of average intelligence), where the matrix is organized according to a four-quadrant disc model where different capabilities are ordered within quadrants with respect to their relative frequency and strength in the population. Take the determinant of that matrix (note that this result should be independent of how you order the matrix elements). We’ll now define that “value” of the bottom of the bowl as “standard normative functioning in the modal pattern”.

Whose Project is This?

Is this what the lab is currently working on? My goodness, no. I would NEVER assign this, in totality, as a project for a student thesis. It requires significant revisions of three or four major disciplines, as well as some advanced mathematics for the methodologies, and new forms of data collection on thousands or millions of persons on a set of variables we don’t even define well, let alone currently measure or collect. But, for the first time, I have been willing to describe a panoramic postcard of this type in a public venue. Why? For years, I was worried that lots of other people would understand, and jump on the problems, and start working on them, and that my best contributions would be left behind, meaningless and trivial. Then I started to think that this would be considered foolish and ridiculous, unless and until I took on myself the responsibility of being able to explain it better so that “most people” could get it. But, Words Spoken to History are not widely understood, even for years or decades, and the measure of the mark on the tree of knowledge is not how many people applaud when the mark is made. Galileo learned this lesson, as did Leonardo DaVinci, and Marie Curie, and Rachel Carson (and Ariane Emory). Am I comparing myself to them? No, not even close. I’m just trying to Speak my Words.

Thank you, C. J. Cherryh, for the concept of sets, and A-E, for the introduction.

May 5, 2017

Returning to Practice

I’ve been interviewing Millennials for work.

In one sense, that is no surprise at all. Many of the students applying for graduate programs stay in the same age range. I have, by contrast, gotten older. Incoming students who were approximately my age (or older) are now the age of my children (or younger). This is the nature of the cycle of life (cue the music from “The Lion King,” which is now considered “Classic Disney”). So, why was this experience different?

First, and most important, was that I was not interviewing people for work in the Lab. These were postdoctoral fellows applicants for Department of State positions. The vast majority of them are still just a few years from their PhD dissertation, experiencing a very different world and context than I did when I was interviewing for my first faculty position. Well, that suggests another difference: I interviewed for a faculty position, and never seriously considered a postdoc. I have spent months engaged with discussions of the role of scientists and engineers engaged in Science Diplomacy, and the interplay of innovation and policy—quite frankly, the education I had come to Washington to have in this very interesting and challenging period. These folks aren’t being recruited to work on my favorite projects, or to have exactly the sort of background I would like a GROUPER to have… but there was still a request from my unit chief for what sorts of people to identify in the stack of resumes and personal statements.

Signs of life.

I was starting to wonder about what that would look like in this context, and in fact, I was starting to question if my time away from the university had left me cynical or unable to see beyond my own narrow daily priorities. Maybe it was a broader sense of unease with the sudden transition from a snowstorm in late March to 90 degree days in late April. Where and how and when was I operating? (I had come to feel a certain sense of stress and negative anticipation regarding my transition back to Purdue, starting in late March when I was requested to provide new course syllabi for my Fall classes. There are new opportunities for next academic year, but after eight months here in Washington, I am neither ready to start right back in on the academic world, nor think in terms of another full annual cycle of activity here.)

And yet, my unit chief wanted me to not only be involved in the interviews, but to craft a few questions for them. It was, as I have said before, a bit different to operate in support of others, instead of being my own “Principal,” but that is part of my learning these days. I’ve also been learning a lot about the differences in cultures of science, and hearing about the distinct experiences of what I have come to call, “Millennial Scholars” (those who may be part of the generation born in 1985 or later, but also have completed their advanced STEM degree programs since 2010). I’ve even produced a few of those people myself, but I already knew enough not to look for people just like Ashley or Karim or Marissa or Jeff (or those who are in the lab now). The discussions in the AAAS meetings in Boston and Washington still had an immediacy and curiosity to me: I was meeting so many people interested in a concept, science policy, that I had long thought was an oxymoron. Why were they interested in this? What new was going on?

What are the challenges and opportunities, strengths and weaknesses, of these Millennial Scholars?

This is, in my experience with the lab, a “signs of life” question. Signs of life it had become a part of my thinking at a time where spring is definitely upon us in Washington. I’m walking much more around the city again, and over the past few weeks, I have been able to enjoy the cherry blossoms and new plants and warm weather. In other words, “signs of life returning” was part of my daily experience.

Figure 1. Signs of life: Tulips at the bus stop

The answers were also informative, as well as reminders of an earlier age. There were those who seemed to have trouble thinking about themselves, and their colleagues, in such a comparative context. However, this compared to several who actually commented about the relative lack of a sense of historical comparison as a weakness of Millennials. What was another weakness? There were several comments about the ease with which new information and new activities and experiences were available, leading to a sense of being dabblers in a variety of skills (“jacks / jills of all trades, masters of none”). In fact, that ease of collecting and novelty even extended to the strengths and weaknesses of networking. Although the world of embassies and interagency discussions and think tank receptions clearly indicates a value to the work of engaging with others… there is a difference between engaging in an effective, distributed knowledge network, and collecting friends and likes as a way of keeping score.

I found myself curiously replaying one conversation in my mind, about the concept that Millennials were more interested in finding ways to align their actions and employment with their passions. Now remember, I lived in Cambridge, MA and California during the 1980s startup crazes, where people were all about passion. I heard the Flower Children talking about living a life of meaning and service. And, most importantly, I have learned how much my career as a professor is actually well aligned with my passion for exploration and sharing what I found.

Figure 2. Albert sharing a sense of passion. Maybe science diplomacy was never so far from my thinking after all. (At the National Academies Keck Center, 500 E St NW)

Was this really different? And then I heard an interesting alternative take on this thought. “Well, if I can’t rely on a pension or Social Security to be around, there is no reason for me to trade boredom for security.” From that discussion, I was transported back to the first few times I taught the course Sociotechnical Systems at Wisconsin. I had known about two different models of work and income as “covenants”: income and status as a way of demonstrating success and favor, or work as a demonstration of one’s passion and artisan’s skills. It took discussion and debate in class for me to learn that there was a large population with a third approach: work was something one does to get enough income to spend the rest of one’s time doing what one really preferred to do. Apparently, lots of people live that way, whether they’re working second shift at the auto parts store, or vice president of global distribution for the auto parts company. I have not chosen to live that way, and I can’t really imagine doing something I hate just to have the income to do what I love, later. Is that what others were assuming we were all doing? Or were others doing this a lot more than I was ever aware?

I felt like I had come full circle in the discussion, and my awareness of my own experience as a young scholar. I am convinced that there are confusions in each generation, not sensing the range or intensity of experience from when prior generations were young and emerging, like new plants bursting into the sunlight and struggling against snow and wind and dangerous frost. I can appreciate it much more now, because I have been in both places, and I have come to feel them both. I am not yet done with the intensity of feeling and learning. And yes, I am still pleased to take a moment on a Spring day and feel the sensual joy of lamb’s ear as I walk from meeting to office or home. Because, even after a great enlightenment, a return to practice and repeat of small things still has value.

Figure 3. Lamb’s ear on 19th St NW. A good reminder of small lessons.

Share this: